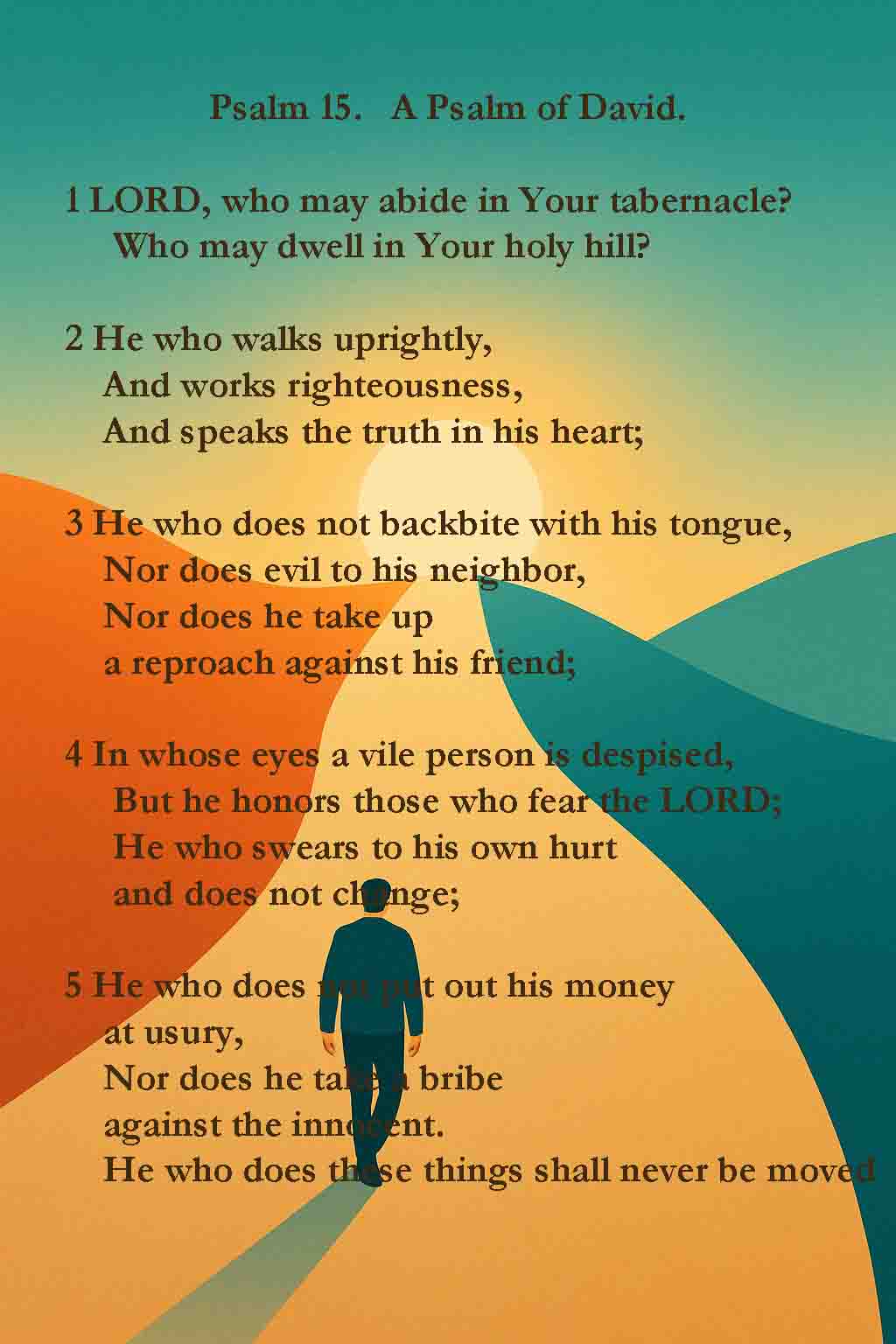

A Review of a Sermon On Psalm 15

The Skewed Anthropology of Therapeutic Preaching:

A Case Study

This article was prompted by a sermon recently

preached in a Presbyterian church in Victoria, Australia. The Preacher presented well, he was articulate, well dressed, had a good manner and was easy

to listen to. He came across as sincere and pastoral, without any sense of

self-aggrandizement. The preacher was theologically trained, although, to my

knowledge, not serving in ordained ministry. Because of this last point, I am

not going to name the preacher or the church where the sermon was preached.

But there was a problem with the content and that is

what this article will address. For this article, I am going to use a term

David Powlison used. In 2007, he wrote an article in the Journal for Biblical

Counselling titled “The Therapeutic Gospel”. In his article he identified five

elements belonging to this therapeutic gospel:

Our need for love

Our need for significance

Our need for self-esteem

Our need for pleasure

Our need for excitement and adventure

To these five gifts we always say thank you. Powlison

made a contrast between the therapeutic gospel and the true gospel where fear

of the Lord rewires us to realise our eternal needs. Powlison believed the

therapeutic gospel was replacing the true gospel in preaching.

So, what’s the problem with the therapeutic gospel

and the preaching of it that Powlison saw had gripped Western preaching?

Therapeutic preaching assumes that humanity’s deepest need is emotional stability, self-esteem, or relief from inner conflict. It views people not as sinners estranged from God, but as wounded individuals needing encouragement and practical tools. Because the starting point is the felt condition rather than the fallen condition, the holiness of God is no longer central.

The biblical truth that sin produces alienation from God (Isa 59:2) and that the human heart is “deceitful above all things” (Jer 17:9) becomes muted. This diminishes both the severity of the law and the necessity of the gospel. God becomes a supporter rather than the Holy One; Christ becomes a helper rather than a mediator.

By contrast, Reformed exposition begins with the holiness of God and the sinfulness of man. It teaches that the greatest human problem is not instability but alienation from God due to sin. It insists that preaching must expose human sinfulness, reveal divine righteousness, and exalt the mediating work of Christ. Application flows from God’s character, not human desire; renewal flows from the Spirit, not moral effort.

The following Table lays the two “gospels” side by side:

Category | Therapeutic Evangelical | Confessional Reformed |

Anthropology | Humanity is emotionally fragile but essentially good; the primary crisis is discouragement or instability. | Humanity is sinful, spiritually dead, estranged from God; the primary crisis is moral unfitness to stand before a holy God. |

View of God | God as encourager, stabiliser, and emotional support. His holiness is not central. | God as holy, righteous, sovereign. His holiness shapes all preaching and exposes human sin. |

View of Scripture | Scripture as a guide for well-being and practical improvement. | Scripture as divine revelation unveiling God’s holiness, human sin, and the path of salvation. |

View of Sin | Sin is an obstacle to flourishing; mainly relational or behavioural failures. | Sin is rebellion against God, corruption of nature, and the cause of alienation from His presence. |

Function of the Law | To reveal areas of personal weakness and guide self-improvement. | To reveal God’s perfect righteousness, expose guilt, and drive sinners to Christ. |

Function of the Gospel | To comfort, reassure, and strengthen the believer emotionally. | To announce Christ’s mediating work, justify the ungodly, and unite believers to Him. |

Role of Christ | Christ assists moral lack; functions as a helper or inspirer. | Christ is the mediator, substitute, true worshipper, High Priest, and fulfiller of all righteousness. |

Ethics | Ethics arise from human example, practical advice, or emotional resonance. | Ethics arise from the attributes of God and flow from union with Christ and sanctification by the Spirit. |

Aim of Application | Emotional improvement, personal stability, relational repair. | Holiness, repentance, gratitude, and Spirit-empowered obedience. |

Pastoral Tone | Encouraging, therapeutic, lightly moralistic. | Reverent, God-centred, convictional, grace-driven. |

Resulting Assurance | Grounded in performance or emotional state. | Grounded in Christ’s finished work and God’s covenant promises. |

This table is general, and it is only a guide. Often, when therapeutic preaching is taking place, it does so deceitfully. By that I mean, in a Reformed denomination, Reformed terms will be sprinkled throughout the sermon, but definitions of terms will be missing. In their place, the “felt needs” of therapy will be inserted.

This happened to me when listening to this sermon on Psalm 15. The sermon ended and I was feeling guilty for being critical of the sermon. But then I asked “what’s going on here”? Something just didn’t seem to hit the mark of biblical preaching.

A table was needed. I printed the transcript of the sermon and mapped out the following.

I narrowed the issue down to the sermon being primarily moralistic, not gospel. Initially, I did not see this. What gave the first clue was the realisation that the preacher never asked “Why it was that David even asked “who may abide in Your tabernacle?”

Category | Evangelical Moralism in the Sermon (Specific to Psalm 15) | Confessional Reformed Exposition of Psalm 15 (What Should Have Been Preached) |

Anthropology | Humanity is fundamentally stable but shaken by life pressures (housing anxiety, disappointments, instability) — the problem is external instability, not internal sin (00:01:05–00:03:06). | Humanity is alienated from God because of sin (Isa 59:2). The central problem is moral unfitness to survive the presence of the Holy One. |

Opening Frame | Psalm 15 is introduced as a pathway to stability — the need for a “firm foundation” is emotional and circumstantial, illustrated by failing at home auctions (00:01:05–00:02:10). | Psalm 15 begins with a sanctuary gate-question: Who may draw near to the God who dwells in holiness? Frame begins with God, not us. |

View of God | God functions as a giver of stability and moral direction; His holiness is not mentioned. God becomes primarily pastoral, not majestic (opening 8 minutes). | God is the consuming fire who dwells between the cherubim. His holiness structures the psalm. God’s presence is both blessing and danger. |

View of Scripture / Function of Psalm 15 | Psalm 15 is taught as a moral blueprint for a stable, integrated life (00:07:29–00:09:08). | Psalm 15 reveals God’s character and exposes human inability to dwell with Him without mediation. |

View of Sin | Sin was not mentioned. Instead, failure of integrity: gossiping, breaking promises, questionable workplace conduct (00:19:46–00:21:04). | Sin is unholiness before a holy God. The psalm requires God’s own righteousness, not merely improved ethics. |

Ethics | Ethics revolve around human integrity — “the integrated life,” interpersonal decency, being consistent, doing the right thing (00:09:08–00:16:43). Ethics are not tied to God’s attributes. | Ethics arise from God’s own being: truthful speech because God is truth; justice because God is just; faithfulness because God keeps covenant. |

View of Holiness | Holiness is absent. No mention of the danger of drawing near to God, no mention of priestly mediation, sacrifice, or divine purity. | God’s holiness explains why Psalm 15 opens with a question. Only the one who reflects God’s righteousness can abide in His presence. |

Law Function | Law exposes moral failure, not spiritual death: “We all fall short of integrity” (paraphrased, 00:23:00–00:24:00). | The law exposes utter impossibility and drives the sinner to seek righteousness outside himself. |

Gospel Function | Christ gives you the righteousness you lack — compared to borrowing a jacket at a restaurant to meet dress code (00:22:47–00:23:41). Christ supplements your lack. | Christ is the true worshipper, the true Zion, the true tabernacle, the true High Priest. He alone meets the requirements of v1 and grants access by His blood. |

Role of Christ | Christ appears late, as a moral top-up. He helps you enter by giving you righteousness-as-ticket. | Christ fulfills Psalm 15: He is the one who ascends the hill; He embodies the character; He mediates God’s presence to His people. |

Aim of Application | “Fix one thing this week,” adjust habits, patch an ethical gap (00:30:37–00:31:10). | Repent of unholiness, behold God’s majesty, draw near through Christ, walk in Spirit-wrought holiness. |

Pastoral Tone | Encouraging, therapeutic, improvement-focused; avoids awe, fear, trembling, or the weight of sanctuary holiness. | Reverent, God-centred, worshipful. Leads to humility before God, gratitude for Christ, dependence on the Spirit. |

Resulting Assurance | Assurance implied through improved integrity and Christ’s moral supplement. | Assurance grounded in Christ’s priestly work, God’s covenant promises, and union with Christ. |

Summary of the Sermon-Specific Patterns

In reality, this sermon exemplifies the classic therapeutic–moralistic structure Powlison identified.

- Begin with human instability

- Redefine the psalm around that instability

- Turn ethics into human integrity rather than God’s righteousness

- Introduce Christ not as priest, but as helper

- Close with a call to self-improvement

This is why the sermon misses the entire sanctuary drama of Psalm 15.

The psalm begins with the holiness of God and ends with the immovability of the righteous —

not because they improve morally,

but because they stand in the presence of the Holy One

under the righteousness of the One who alone may ascend.

The sermon finished with an account of the preacher’s father who had died 2 years earlier with his integrity intact. The Psalm concludes with the righteous person being immoveable.

So, a question that arises here, is why did this Psalm get reinterpreted with such distortions?

Why Evangelical Moralistic Readings of Worship Psalms Are So Common

Evangelical preaching in the modern era has absorbed a cultural instinct: begin with the hearer, not with God. This instinct arises from a therapeutic anthropology — the conviction that people are fundamentally well-meaning but emotionally fragile, and therefore most preaching must comfort, stabilise, or uplift. Within this framework, the holiness of God becomes an unwelcome intrusion because it confronts rather than soothes. Thus, texts like Psalm 15 are subtly reshaped. Instead of asking, “Who may dwell with the Holy One?”, the sermon asks, “How can I become a more stable and integrated person?”

There are several reasons this misreading is so common:

1. A diminished view of sin

When sin is reduced to relationship fractures, bad habits, or lapses in kindness, psalms that demand righteousness are interpreted as calls to moral improvement rather than revelations of divine holiness and human unfitness. This produces sermons heavy on exhortation but light on repentance and awe.

2. A functional loss of the doctrine of God

Where God’s holiness is neglected, the sanctuary imagery of the psalms dissolves. The tabernacle no longer represents dangerous proximity to the blazing purity of God but becomes a metaphor for inner stability. Without a towering theology proper, moralism fills the vacuum.

3. A sentimental view of Scripture

Instead of seeing biblical poetry as God’s self-revelation, many preachers approach psalms as mirrors of human experience. Application becomes human-centred rather than God-centred. The psalm is made to speak to the anxieties of the listener rather than the majesty of God.

4. A truncated Christology

If Christ is primarily the one who “helps me live better,” then Psalm 15 must be reinterpreted to serve that end. Christ becomes moral reinforcement rather than High Priest, Mediator, and true Worshipper.

5. Pressure to produce practical sermons

Many evangelical churches expect Sunday preaching to yield immediate, actionable steps. This creates a bias toward behavioural modification and away from God-centred contemplation. Psalm 15 becomes “five qualities of a righteous person” rather than “the terrifying beauty of God’s holiness and the righteousness He demands.”

6. A pedagogical focus on relevance rather than revelation

Preachers are told to “meet people where they are,” which can be wise, but when overused, or the fallen condition of mankind is ignored, this counsel results in sermons that remain where people are and never lift them to where God is. The congregation is left with therapeutic encouragement rather than transcendent truth. In Reformed parlance, Arminianism marks the resultant sermon.

Together, these tendencies, as seen in the sermon under discussion, hollow out the psalm’s theological core. What was meant to humble the worshipper at the gate of God’s dwelling is transformed into a self-help lesson in integrity. The sanctuary becomes a metaphor; holiness becomes optional; Christ becomes a tool. The tragedy is that the glory of God is obscured and the true power of the psalm is lost.

How can such errors be avoided? Giving the context of the Psalm here would have significantly helped.

Psalm 15 is a sanctuary psalm — a gatekeeper psalm. It confronts the worshipper with the inescapable truth that God is holy and sinners cannot dwell in His presence apart from true righteousness. Preaching it faithfully requires guarding against subtle but common missteps.

Below are a few applicatory points for illustration purposes taken from this sermon.

1. Begin With God’s Holiness, Not Human Need

Wrong starting point:

“What do people feel today? How can this psalm speak to their instability?”

Right starting point:

“What does this psalm reveal about the God who dwells in holiness?”

The preacher must not begin with sociology or psychology but with theology.

Psalm 15 opens with a question about access to God, not about emotional stability.

2. Frame the Psalm as a Question of Access, Not a Path to Self-Improvement

Psalm 15 is not a checklist for moral living.

It is a theological crisis:

How can any sinner survive the presence of the Holy One?

Since this was not the frame, the sermon collapsed into moralism.

3. Let the Ethics Arise From God’s Attributes

The qualities in vv2–5 are not human virtues but reflections of God Himself:

- He is upright → we must walk uprightly

- He is truth → we must speak truth

- He is faithful → we must keep our word

- He is just → we must refuse exploitation

Without grounding ethics in the character of God, the sermon became humanistic.

4. Recover the Sanctuary Imagery

Help the congregation feel the distance.

Bring them to the doorway of the tabernacle:

- the veils

- the altars

- the holy presence

- the priestly mediation

- the blood and the sacrifice

This is the biblical world Psalm 15 inhabits.

The sermon omitted all of this and the psalm lost its theological gravity.

5. Resist Premature Application

Do not rush to “fix one thing this week.”

Do not leap to relationships, promises, speech habits.

Application without revelation is moralism.

First lift up God.

Then lower man.

Then show the impossibility of entry.

Only after the law has done its work should the preacher proceed.

A right relationship with God first will naturally lead the Holy Spirit to bring conviction upon your heart as to what relationships you may need to attend to this week.

6. Introduce Christ Only When the Weight of Holiness Has Fallen

In this sermon, Christ was summoned far too soon to soften any blow.

Let the text first silence the hearer and bring conviction.

Let the righteousness required stand tall and terrifying.

Then bring Christ in as:

- the true Worshipper

- the only One who may ascend

- the One who perfectly fulfils vv2–5

- the High Priest who enters for us

- the Mediator who brings us in by His blood

This avoids Christ being a helper and presents him as the fulfilment of the psalm’s demand.

7. Preach the Law–Gospel Rhythm of the Psalm

Psalm 15 is law in structure and gospel in resolution:

- Law: You cannot enter.

- Gospel: Christ enters and brings you with Him.

- Sanctification: The Spirit produces in you the character of vv2–5.

- Assurance: “He shall never be moved” is grounded in Christ, not you.

Biblical doctrines were ignored in this sermon. No word studies were provided. This led to the sermon dangling in the air, rather than grounded in God.

8. Close With Worship, Not Advice

The end of Psalm 15 is not:

“Go try harder and mend one relationship this week.”

The end is:

“Stand in awe of the God who receives sinners through His appointed way.” The immovability of v5 is a work of God upon the person who asks the questions of v1. Properly understood, this leads to true worship.

A confessional preacher leaves the congregation not feeling improved but humbled, assured, and grateful.

Conclusion: Psalms in General

The psalms set before us the God who dwells in unapproachable light, and they teach the soul to tremble before drawing near. These sacred songs are not merely expressions of devotion, nor are they instruments of comfort alone. They are revelations of the Holy One who sits enthroned between the cherubim (Ps 80:1), before whom the earth shakes (Ps 99:1), and whose name is holy (Ps 111:9). In them the Lord reveals His glory, and by them He trains His people to know that access to Him is no common privilege.

The psalms also display the necessary preparation for approaching God. The psalmist speaks of clean hands and a pure heart (Ps 24:4), of truth in the inward parts (Ps 51:6), of righteousness, justice, and uprightness (Ps 15:2–5). These are not adornments of religion but requirements of the God who is light and in whom is no darkness at all (1 Jn 1:5). The sacrifices offered in the temple were but shadows of the deeper truth that God seeks holiness in the heart of the worshipper. “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit” (Ps 51:17), for contrition confesses both His holiness and our sin.

Yet the psalms do not leave us at a distance. They also reveal the mercy of God who makes a way for sinners to approach Him. The psalmist recounts how the Lord forgives iniquity, covers sin, and imputes no transgression to the humble (Ps 32:1–2). He speaks of the God who redeems His people from all their troubles (Ps 34:17), who leads them with His strength (Ps 23:3), and who receives them into His presence with joy (Ps 16:11). Holiness does not hinder mercy; it shapes it. God’s mercy is holy mercy, extended through the means He appoints and in the manner He commands.

Thus, the psalms train us to approach the Lord with fear and with confidence, knowing both His majesty and His grace. They call us to examine our hearts, to cleanse our hands, to put away deceit, to walk in righteousness, to love His commandments, and to delight in His presence. They reveal God as the Holy King, the righteous Judge, the faithful Shepherd, and the merciful Redeemer.

And as the light of revelation grows through the canon, these psalms lead us to expect the One who shall perfectly fulfill their demands. They teach us to long for the righteous Man, the true worshipper, the One who shall ascend the hill of the Lord without guile in His heart and with truth in His inward parts. In Him the holiness of God is displayed without measure, and through Him sinners are brought near to dwell with God for ever.